“Sound as medicine is nothing new. Sound as medicine has

been used for hundreds of years on all continents. For

example, Tibetan throat singers use vibration to heal,

shamans in Latin America use flute and singing and many

other instruments, and percussion instruments used in Africa

are some of the examples of how sound is used as medicine.”

– GUADALUPE MARAVILLA

RESEARCH

The theme “Não Foi Cabral” represents a challenge to the traditional historical narrative associated with the arrival of Pedro Álvares Cabral (a Portuguese navigator) in Brazil in 1500. In fact, this arrival is generally and incorrectly considered the “discovery” of the country.

Thus, this theme suggests a deconstruction of that narrative, proposing a broader reflection on the formation and identity of Brazil. Moreover, it also points to a critique of the Eurocentric view of Brazilian history, highlighting that the formation of the country cannot be reduced to a single event or figure. The theme leads to a search for a deeper understanding of Brazil’s roots and identity, exploring Indigenous, African, and other elements that played significant roles in the country’s formation.

In line with this, the theme addresses contemporary contradictions and criticises self-destructive practices in Westernized societies, suggesting that artistic mediums can be seen as refuges that allow civilizations to heal through connection with different perspectives.

Furthermore, according to Bevilaqua, Patrícia Magalhães and Frederico Tavares Junior (2023), “(...) the dissemination of ancestral Indigenous knowledge through technological access allows arts, rituals, cosmovisions, spiritualities, and relationships with the world to be transported into virtual spaces and times with broad reach, thus enabling more effective resistance to the impositions of colonizing thought, as well as mitigating prejudices about these populations and their knowledge.”

Thus, I consider that this theme can also serve as a starting point to introduce some of these rituals, arts, and spiritualities in order to mitigate prejudice toward Indigenous peoples and their knowledge.

Thus, I consider that this theme can also serve as a starting point to introduce some of these rituals, arts, and spiritualities in order to mitigate prejudice toward Indigenous peoples and their knowledge.

In summary, “Não Foi Cabral” suggests a reinterpretation of Brazil’s history and the pursuit of a broader and more inclusive narrative that recognizes the multiplicity of influences and contributions to the construction of the nation’s identity.

My project aims to use Indigenous resistance as a starting point, harnessing the power of sound and movement to heal the wounds of the past and cultivate compassion and understanding in the present. It is an immersive experience that invites the audience to connect with history in a profound way.

For this project, I intend to sculpt iron and ceramic instruments inspired by Indigenous instruments. The contrast between the ceramic instruments, which produce soft and resonant tones, and the iron instruments, which create metallic and deep sounds, is something I would like to explore. This fusion of sounds is also quite common in Indigenous rituals (e.g., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5j_b0kjuH4Y). In this example, the “Mantra Canto da Floresta,” you can hear wind instruments (sometimes ceramic) mixed with percussion instruments (which are sometimes made of iron).

Music was an essential element of Indigenous life, as it was an important component of communication and was present in socio-religious manifestations, ceremonies, work routines, lullabies, among others. It was not merely an accessory, but an integral part of the culture and daily life of Indigenous peoples. (Nunes, K. M., 2016)

The choice to incorporate atonal music into this project adds an intriguing and provocative layer to the narrative I have constructed. Atonal music, characterized by the absence of traditional tonality, offers an unconventional sonic approach that can amplify the emotions and intensity of the experience. By moving away from traditional musical structures, atonal music evokes a wider range of emotions, often challenging the audience’s auditory expectations.

The fusion between the iron and ceramic instruments (sculpted and inspired by Indigenous instruments) gains an even more intriguing dimension with the inclusion of atonal music. The contrast between the soft, resonant tones of the ceramic and the metallic, deep sounds of the iron can be enhanced by the unique expressiveness of atonality, creating a complex and captivating sound environment.

This musical choice not only challenges the traditionality often associated with the representation of Indigenous culture in music but also allows for a deeper exploration of the emotions and sensations that can be conveyed through sound.

FIRST EXPERIMENTS:

The first instrument, built from iron and equipped with a saxophone mouthpiece, offers a unique combination of metallic and melodic sonorities. The fusion of these elements results in an expressive timbre that challenges traditional expectations.

The second instrument, also constructed from iron, features a kazoo mouthpiece, adding a more playful and peculiar element to the sonic mixture. The metallic resonances intertwined with the kazoo’s buzzing tone create contrast, contributing to the experimental atmosphere that characterizes atonal music.

Throughout the working process, I considered to integrate microphones to capture the sounds of the instruments during the performance and place them in a loop, as this would “fill” the sonic dimension but the final result for the most of the exhibitions of this project ended up being the music I produced with these intruments on loop without the performative part.

This experience propelled me toward atonal music, where expressive freedom is unlimited and where traditional tonal boundaries are challenged. I eventually found a unique form of communication, capable of transcending the borders of the familiar and opening a path to an unexplored sonic territory, where authenticity and innovation coexist.

This project also marks a new direction in my artistic practice. Until now, much of the music I enjoyed listening to and performing in recitals was extremely tonal and harmonic—from Mendelssohn to Rachmaninoff

(https://www.facebook.com/casadamusica/videos/542979163391760/?locale=pt_PT). It was during my undergraduate studies in Sound and Image that I had the opportunity to experiment with various types of media and break patterns I had been following since the very first day I played the piano.

(https://www.facebook.com/casadamusica/videos/542979163391760/?locale=pt_PT). It was during my undergraduate studies in Sound and Image that I had the opportunity to experiment with various types of media and break patterns I had been following since the very first day I played the piano.

ATONAL MUSIC

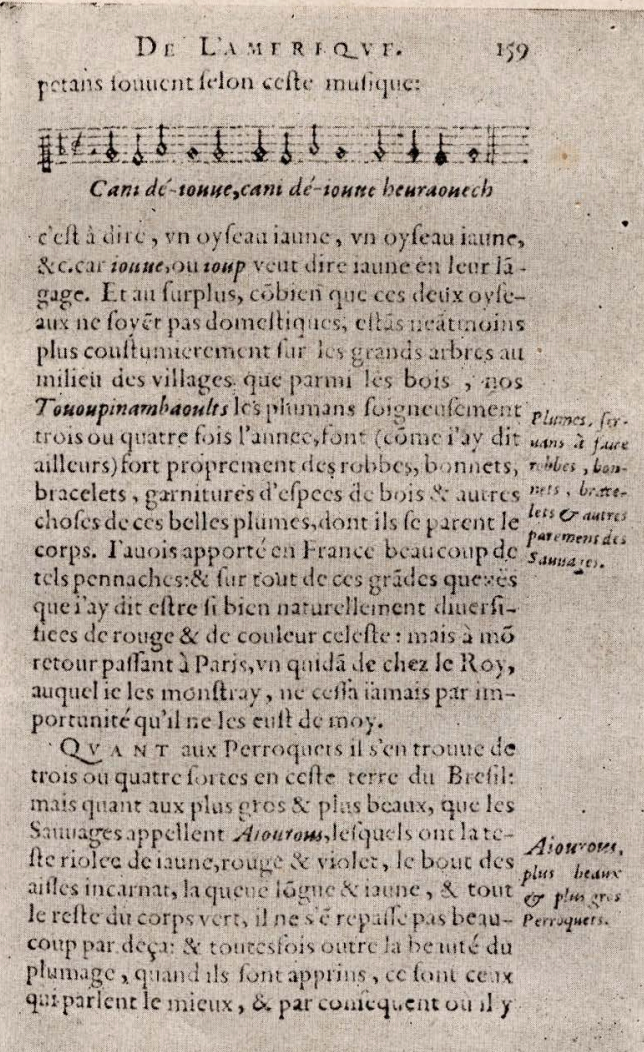

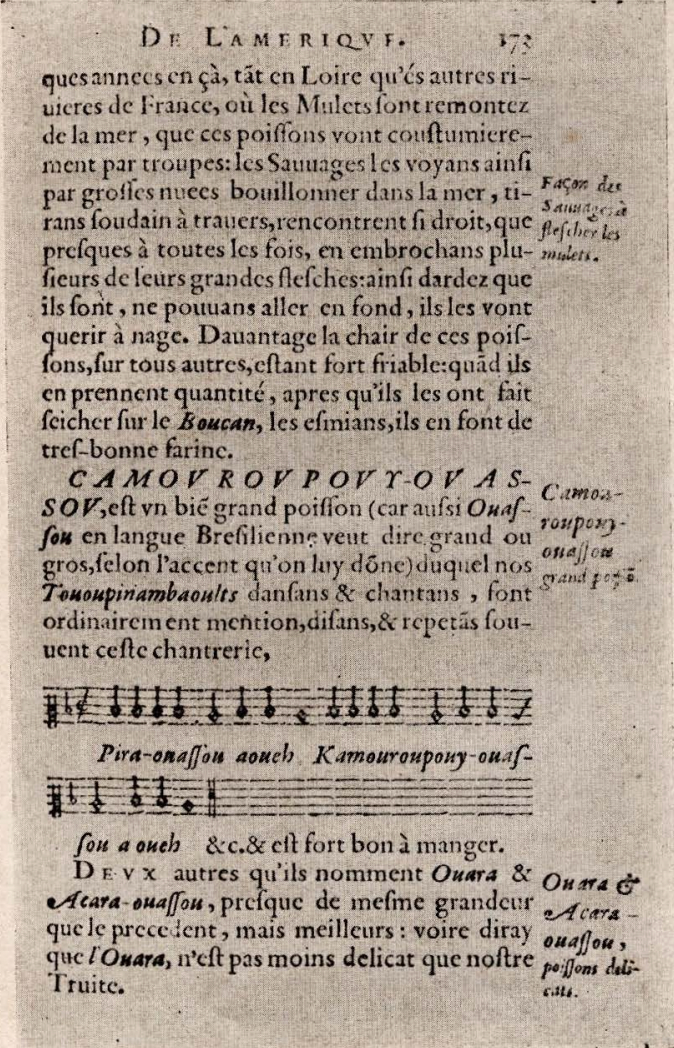

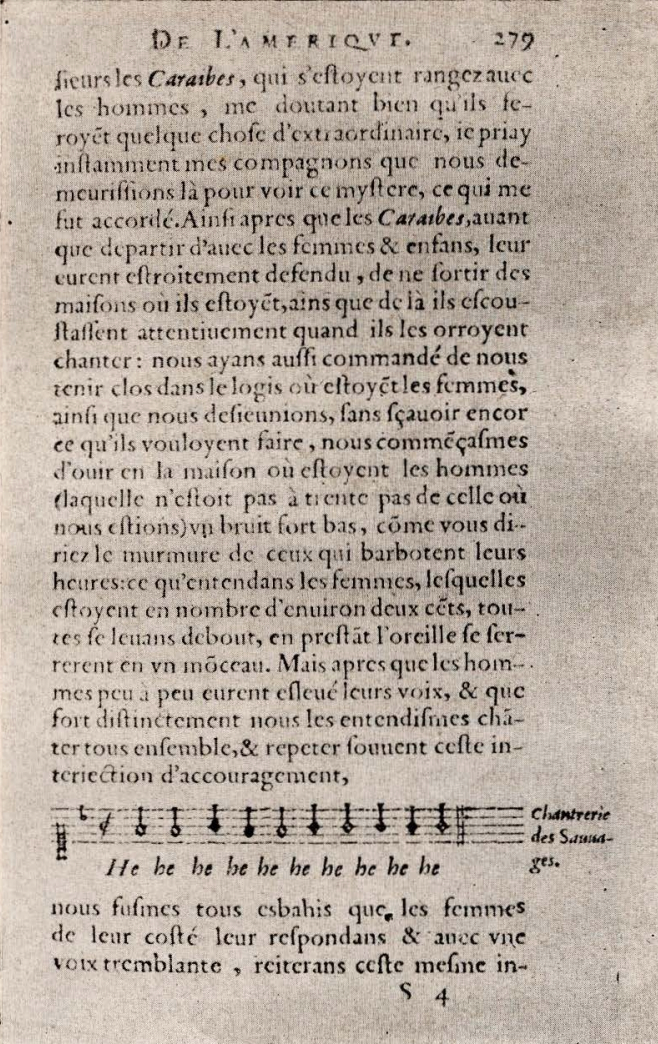

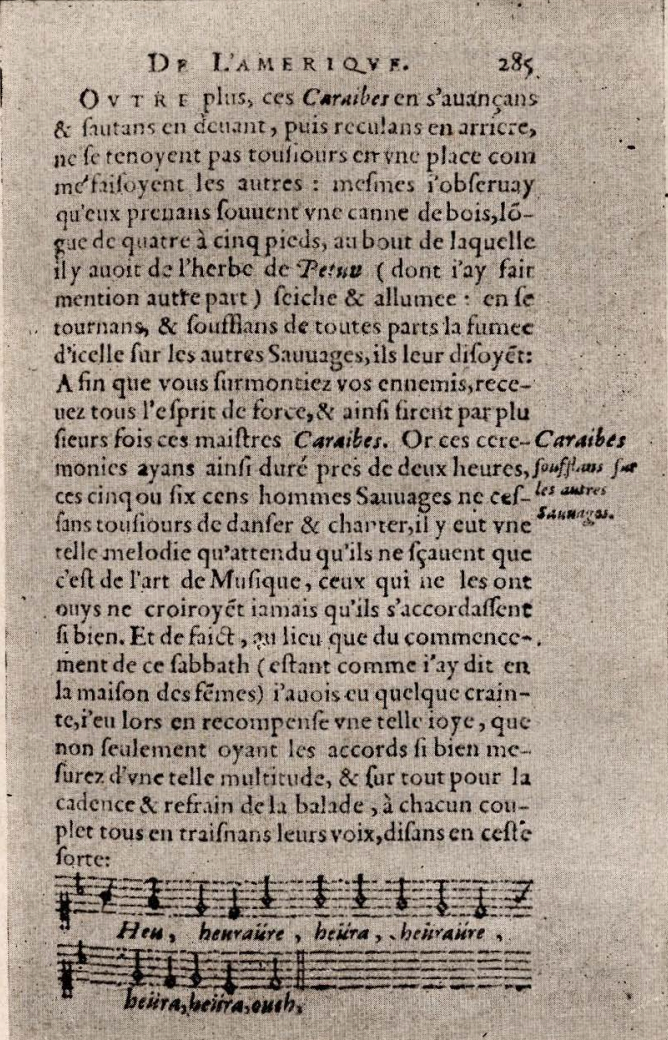

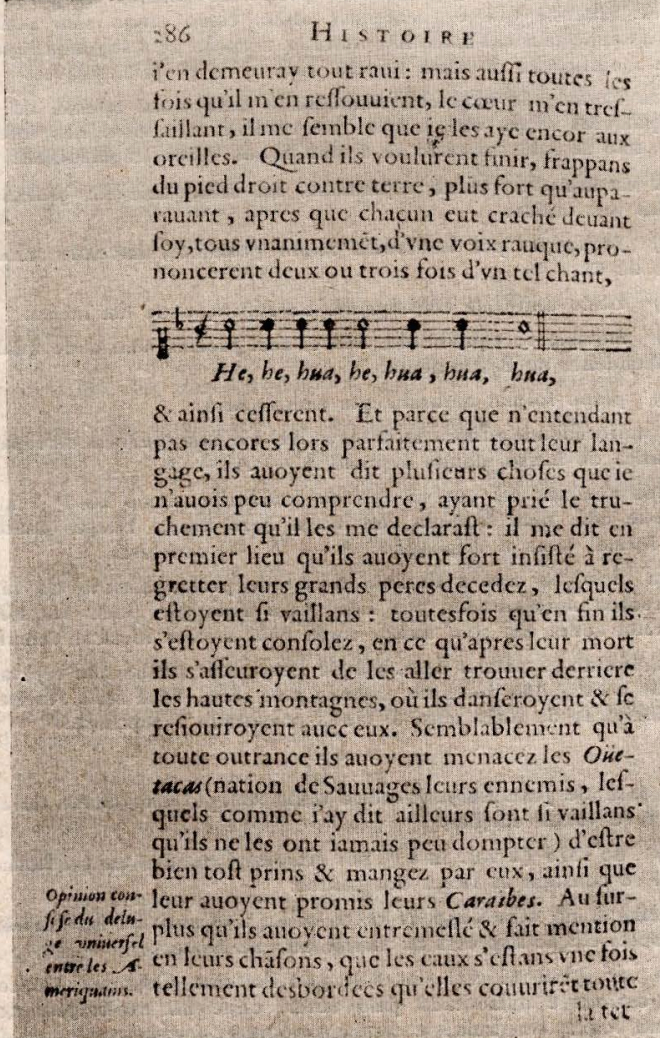

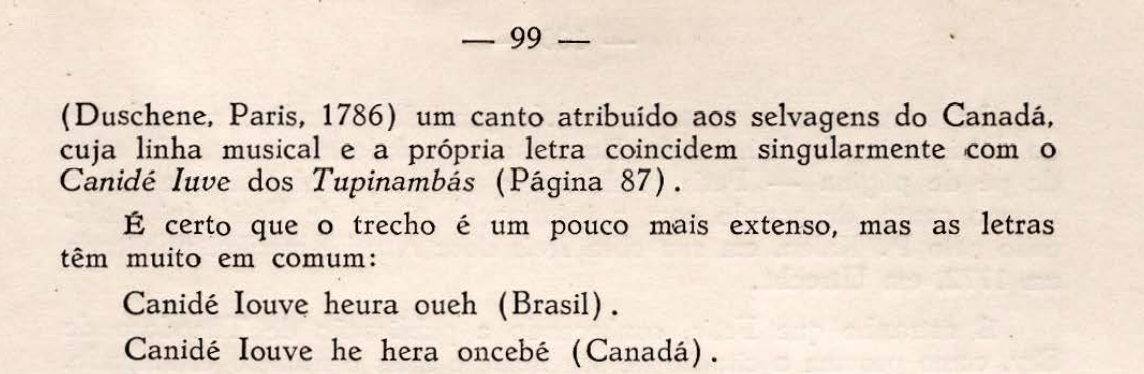

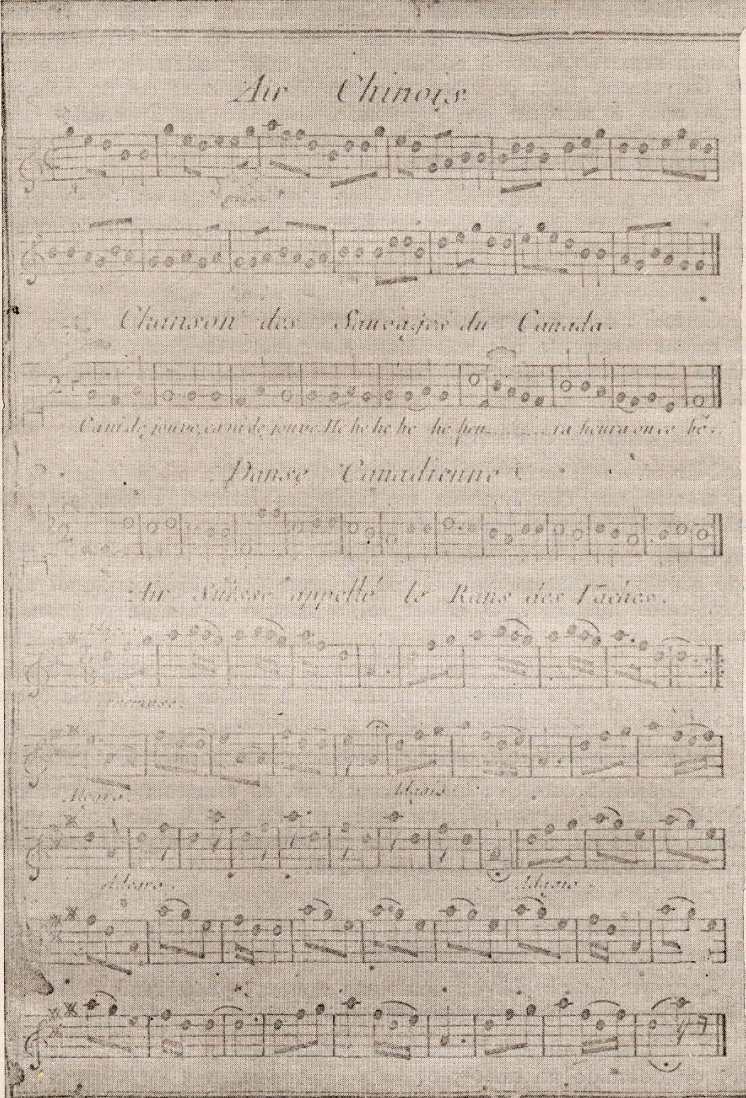

Regarding the music composed by Indigenous peoples during the colonial period, information exists only in written documents derived from the narratives of colonizers. These writings are limited, as they served the colonizers’ own interests and promoted interpretations filled with prejudice. Likewise, the graphic records that exist do not consider musical particularities, basic structural elements, or what is truly authentic in this music (Nunes, K. M., 2016).

Based on the available accounts of Indigenous culture, it is possible to describe the connections between dance, music, the use of instruments, and Indigenous rituals. However, despite all the descriptions, those observing these peoples lacked both the ability and the interest to transcribe any form of music, which significantly reduced the amount of material specifically relating to musical practices.

Luciano Gallet, a Brazilian musician that studies Indigenous music, demonstrates in his article Estudos do Folclore the similarities between the characteristics of Indigenous cultures in the 1930s and at the beginning of colonization. With regard to music specifically, he states that: “The same findings of similarity and unity of primitive character are confirmed in Indigenous musical themes of both the ancient and modern periods, recorded at the time of the earliest encounters.”

Helza Cameu, in her book Introdução ao estudo da música indígena brasileira, explains that despite the limited amount of information on colonial-era music, even though Indigenous culture today has adopted many new instruments, this does not affect its traditional culture: “The introduction of foreign instruments is still not a reason for abandoning those that are typical of their culture, for they can perfectly distinguish the traditional from the incorporated. As for music, although most information goes no further than description or personal impressions, the documents collected so far demonstrate a consistency in the formative elements of both vocal and instrumental music of the past and present.”

Animism is the minimal definition of religion as a “belief in spiritual beings.” This religion originated from the attribution of life, soul, or spirit to inanimate objects. According to this theory, Europeans moved from animism to polytheism, then monotheism, thus progressing from a state of nature to a state of civilization. In contrast, Indigenous peoples of North and South America, Africa, Asia, and Polynesia chose, during this process, to remain in what European perspectives labeled “primitive survival” in their natural state (Martin H., 2012).

INDIGENOUS MUSIC REGISTRIES

CONCLUSIONS

Through the project Beyond the Unseen, I had the opportunity to explore the intersection between sound and sculpture. It was a project that allowed me to develop my artistic abilities both in terms of visual creation and sound composition, as well as in the overall assembly of the exhibition.

During the exhibition setup, I was able to improve my ability to solve problems that might arise at the last minute (for example, adapting the piece to the space). In addition, I was also able to look at the work with more distance and understand what I would like to change in the future (such as the number of modulations present in the sound composition).

I also believe that, in developing this project, particularly during the pre-production phase, I managed to acquire a strong theoretical foundation regarding the theme “Não Foi Cabral”, and from that point on, I was able to connect certain concepts or artistic models with my installation.

In this way, through this project, I was also able to develop a deeper interest in multimedia art. It was a project in which I experimented with various ways of exhibiting, composing sounds, and shaping ceramics, and in the end, I was very content with the final installation.

REFERENCES

GUADALUPE MARAVILLA – PROVOCATIONS

(https://icavcu.org/exhibitions/provocations-guadalupe-maravilla/)

(https://icavcu.org/exhibitions/provocations-guadalupe-maravilla/)

ABOUT PROVOCATIONS

Maravilla created totemic sculptures using steel, gongs, and materials he collected along the U.S. Mexico border and in Central America reconstructing part of his own migratory journey. The sculptures were activated through performances, rituals, and workshops that use sound, movement, and human connection as vehicles for healing and exchange, beginning with a twelve-hour sound bath ceremony to open the exhibition.

Guadalupe Maravilla believes in non-Western forms of healing including gongs and spiritual rituals. In this project, the intestines become a locus of stress and illness, echoed in the winding formal qualities of his drawing, sculpture, and performance. Bringing together themes and forms that resonate and reinforce one another across different parts of the project, Disease Thrower enacts gestures and rituals that can help heal both the human body and the social body.

GALERIE MAZZOLI - UNTITLED, FLUTE, CHAIR, MASKING TAPE, ASSISTANT - (EMERGENCY SOLOS)

(https://www.v6.facebook.com/GalerieMazzoli/photos/a.2143694782531407/3056642111236665/type=3&source=48&paipv=0&eav=AfY_PWFmKf-sB2xafiZso-fBj2zubwtfaxww8_Gd75yXlpkRqPe5n7YQ0J1JsckLC5g&_rdr)

ABOUT EMERGENCY SOLOS

One segment of the 'Emergency Solos, a collection comprising eight flute and objects performances. These pieces were executed by Christina Kubisch during the periodfrom 1975 to 1978.

“Christina Kubisch’s work contributed to the beginning of an interdisciplinary attitude towards sound-based art making that paved the wave for generations of artists to follow, and it represents an essential part of the history of what we now call “sound art.”

VIDEO / DOCUMENTARY REFERENCES

Lygia Clark (1984), Memory of the Body

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ML_NP3s5Nqo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ML_NP3s5Nqo

Guadalupe Maravilla (2021), Guadalupe Maravilla & the Sound of Healing

https://art21.org/watch/new-york-close-up/guadalupe-maravilla-the-sound-of-healing/

https://art21.org/watch/new-york-close-up/guadalupe-maravilla-the-sound-of-healing/

Folha de S.Paulo (2022), Lygia Clark’s Performance Applied as Treatment in a Psychiatric Center in Rio de Janeiro

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TQDvMe68feI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TQDvMe68feI

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Bevilaqua, P. M., & Junior, F. T. (2023). Noopolitics of Consumption and Colonization: Resistances and (Re)existences in Contemporary Indigenous Art. Proa: Revista de Antropologia e Arte, 13, e023005-e023005.

Cameu, Helza. Introduction to the Study of Brazilian Indigenous Music. Conselho Federal de Cultura e Departamento de Assuntos Culturais, 1977.

Luciano Gallet (2023). Studies of Folklore, Itaú Cultural de Arte e Cultura Brasileira. São Paulo.

Martin H., Sonja O., Julia A., Lars L. (2012). Animism, Haus der Kulturen der Welt.

Nunes, K. M. (2016). Notes on Indigenous Music and Culture: From a Colonizing Approach to the Contemporary Hybrid Sound. Travessias, 10(1), 112–124.

Tomaz, R. F. (2022). Animism, Perspectivism and…